Tintin: My Dinner With Hergé

An essay about the artistry of the Tintin books in the form of a conversation between two Tintinophiles: comic artist, Hugh Todd, and myself. (The title refers to the film My Dinner with André in which two artists ‘re-create’ conversations they’ve had about art).

Raymond: As a child I loved Tintin because it had everything that other children’s books didn’t in the 1960s: adult characters, comic strips, reality (people died, got drunk, shot guns), reanimated mummies – and the cinematic effect of being swept along in Tintin’s adventures.

My mum volunteered in a small children’s library in Christchurch (yes, the 60s were great), and I’d snaffle the returned Tintins before they were shelved and hide them in the office to read at my leisure. They also marked my transition from dull school readers to real language: “Ectoplasms! Sea-gherkins! Iconclasts!”.

You were even more Tintin-obsessed as a child; is that right, Hugh?

Hugh: Despite what my mum said about never ‘using’ friends — and somewhat to her despair, I think — I would often visit some friends’ houses and disappear into their comic collections.

Tintin was best of all. Because Tintin comics were quite expensive (they were all in hardback in those days) the rare people who had extended or even complete collections were like the keepers of the Crown Jewels.

I don’t know how you compare obsessions, but reading comics did lead me to want to draw them, and I came up with characters of various sorts of my own. And eventually, in my mid twenties, I spent four years working as an editorial cartoonist on a The Otago Daily Times; not comics, but it was a living made from drawing, which was wonderful.

Going back to the appeal of Tintin… I think this has changed subjectively from when I was a child of seven being given The Seven Crystal Balls. Then I think the humour was less obvious to me. But the stories were exciting and vivid, and the scenes depicted in the drawings felt astonishingly real. Apart, that is, from the yeti in Tintin in Tibet and the ape in The Black Island.

I remember in particular the den of one of the explorers in The Seven Crystal Balls, Mark Falconer. Such loving and evocative detail. The architecture, the artefacts, the furniture, even the look of the man were just right. You could lose yourself in such a perfectly realised world.

Hergé was also a master of evoking atmosphere. Think of the house of Professor Tarragon in the same book, gated and protected by security: the building of the storm, the heat leading to the burst tyre, the gust of wind as depicted by a slender tree against a slate grey sky, the sinister Rascar Capac mummy in his cabinet, the ball lightning, Tintin’s nightmare… such a feeling of supernatural dread evoked by a confluence of natural events.

How about you, Raymond, do you think the Tintin books affect you differently now from the way they did then?

R: To respond to you first: I like your ‘Crown Jewels’ image – the books were precious items, their ‘beauty past compare’. I always felt so sorry for Ranko the ape (not because of how he was drawn) and I suppose that was enough to make the character real for me. And Rascar Capac is one of the most terrifying characters in children’s literature – I thought then he wasn’t just a dream, but had really come to life. You could say Tarragon’s house was under a real curse: when Hergé sketched the actual villa in Brussels he was unaware the house was occupied by the SS.

R: To respond to you first: I like your ‘Crown Jewels’ image – the books were precious items, their ‘beauty past compare’. I always felt so sorry for Ranko the ape (not because of how he was drawn) and I suppose that was enough to make the character real for me. And Rascar Capac is one of the most terrifying characters in children’s literature – I thought then he wasn’t just a dream, but had really come to life. You could say Tarragon’s house was under a real curse: when Hergé sketched the actual villa in Brussels he was unaware the house was occupied by the SS.

Do the books affect me differently now? Yes. As an adult I’m more interested in the illustrations and fascinated by the backstory – especially the way each Tintin book reflects the politics of its time: for example, The Shooting Star (1941) expresses the apocalyptic, wartime mood. Most touching, I think, is the backstory of Tintin in Tibet (1958): Tintin’s search for Chang mirrors Hergé’s bond with the real Chang Chong-Jen.

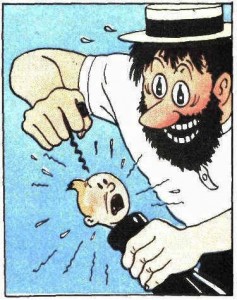

As a child I wasn’t consciously aware of the drawing style (as you were, with your budding artist’s eye) and I’d skip over historical or technical references, such as the Japanese politics in The Blue Lotus (1938). Back then I loved the cliffhangers and the slapstick humour. In Crab with the Golden Claws (1940) it was the hapless crew being thumped by Allan – I still recall Hergé’s brilliant set-up lines like, “It’s a rum thing, Mister Mate!” – and Haddock’s drunken ‘rantics’ (invented word). I love the eye-popping image of Haddock about to corkscrew Tintin’s noggin. Crab is the first book I read and remains my favourite, character-wise at least.

over historical or technical references, such as the Japanese politics in The Blue Lotus (1938). Back then I loved the cliffhangers and the slapstick humour. In Crab with the Golden Claws (1940) it was the hapless crew being thumped by Allan – I still recall Hergé’s brilliant set-up lines like, “It’s a rum thing, Mister Mate!” – and Haddock’s drunken ‘rantics’ (invented word). I love the eye-popping image of Haddock about to corkscrew Tintin’s noggin. Crab is the first book I read and remains my favourite, character-wise at least.

Now the big question, Hugh. What did you think of the Spielberg/Jackson movie treatment of the Crab and Unicorn books?

H: I should say I’ve read some of the reviews, including one in the Guardian, which may influence what I say.

It’s hard for me, as someone who has grown up with the books, to put myself in the shoes of someone encountering the story for the first time. Would I be more delighted with the movie if I was coming to it fresh? I don’t know.

That’s not to say I disliked the movie. I quite enjoyed it, and found myself laughing at several points. The opening credits were lovely. It was a nice touch to bring Hergé back to life in the street market scene.

[R: Yes! The Hergé sketching scene announces the transition from comic to movie (to me, it said, “relax”). Tintin says that the sketch “captures something of me” – an accurate review of the movie.]

H: But there is something about the books that is captivating in a way the movie is not. When I saw the first images and snippets of the movie, I was afraid the real-but-cartoony look and movement of the characters might be too off-putting. In the event they weren’t as bad as I had feared. The realistic eyes still jarred, set as they were in non-realistic faces. The clothes, and Snowy’s fur, had a strange glued-on look about them. Hergé was able to convey the look of real fabric (and Snowy’s fluffiness) in just a few well placed lines. Of the characters the Thompson Twins, in particular, looked grotesque, with their outsized feet and puffy faces. Hergé’s characters were properly proportioned. None of this was awful enough, though, to detract fatally from the movie.

I was not convinced by the elaborate action sequences. 3D software has made it possible to create movies in which anything at all can happen… and often does. There’s a lack of restraint. It‘s as if film-makers believe they have to keep topping each other’s confections. And the trouble is, it has become very difficult to impress us with it all. It fails to convince, because it departs so brazenly from reality.

Compare the movie’s chase sequence — in which the clues to the treasure change hands in a series of preposterously engineered events — with the sabotaged train sequence in Prisoners of the Sun. Though less happens in the latter, what does happen is within the bounds of credibility — which makes Tintin’s peril, and resourcefulness, all the more real. I seem to remember spending quite some time pondering Tintin’s jump from the viaduct: the angle of fall, the terrible distance, the choice between certain death on the train versus this almost equally dangerous leap… Though it is just a single frame on a page, its import was enormous. There was Tintin suspended in space, caught between life and death. An eternal moment. In a movie, such an event is over almost immediately, and the plot rushes on.

Perhaps this is why, despite the cinematic quality of Hergé’s stories, Tintin’s true home is in the comic book medium. He occupies a space at a perfect level of abstraction, real enough to evoke our world, pared back enough to activate the imagination. A movie, particularly with the strange hybrid comic/real characters of this one, unbalances this equation. It fills out both the action (leeching out the tension that individual drawings can evoke) and the characters themselves, intruding on our own imaginative partnership with the art.

R: Agree about the chase sequence – Spielberg shamelessly rehashing Indiana Jones, plus the spinning propeller scene (but I did love his Jaws-quiff gag). That aside, it’s one of his better films and I was surprised I enjoyed it so much. Characters, acting, script, and visuals all meshed agreeably.

I’d been worried that ‘my’ Tintin (the book in my head) would be ‘intruded’ upon. But two things won me over: the motion capture, and that the spirit of the books was honoured. I think motion capture is the ideal medium for a ‘moving’ version of the Tintin books. The technique is a fusion of reality and computer, a nice parallel with the books which were a perfect fusion of reality and comic art. Which leads me to the title for this conversation: the movie My Dinner with André was also a seamless weave of fact and fiction (two artists recreating a real conversation).

You pay eloquent tribute to the way Hergé ‘activates the imagination’, but I think movies operate differently. Which brings in my second point: the movie adaptation respects the source material. Think of the great movie versions of Roald Dahl books – The Witches and Fantastic Mr Fox – which found new dimensions (of horror and charm respectively) but retained Dahl’s spirit. ‘A good adaptation involves a conversation between artists’ (Anton Bitel) – and Jackson and Spielberg have richly interpreted many key scenes from the books: the Karaboudjan action, the desert crash, duelling Red Rackham.

Tintin’s character was also consistent with the book; an idealist rather than a quipping celebrity. And still enough of a ‘blank domino’ (Michel Serres) for the viewer to identify with him. I was relieved the movie changed/adapted the plot and softened some adult themes to a PG rating. It means children will come ‘home’ to the books to find the full story: Haddock corkscrewing Tintin, cans of opium, and the Bird Brothers.

I think mainstream movies are more of a shared experience. But we own books. We read the Tintin books at our own pace, lingering over a single frame (as you say), flicking back and forward, re-reading the jokes. The book becomes our own, wired in our imagination, linked with real places (Mum’s library for me) – the eternal advantage of books over movies.

Are Hergé and Tintin relevant today? Or will the juggernaut movie series gradually smother the books?

H: My theory is that the art of the comic book Tintin is pure and modernist enough to be timeless. It doesn’t really matter that all of the vehicles are from another era, for example (much as we used to delight in recognising them when we were young) because Hergé’s art itself hasn’t dated.

And a good story is a good story. The characters are vivid, the gags just as funny as ever, the plots just as engaging. Our nephew’s walls are covered in Tintin posters: the Hergé kind. So maybe there are enough serious, enquiring bookworm boys (I’m not sure that girls would ever have as much affinity for Tintin) to keep Tintin the comic book character alive far into the future.

Perhaps what the films do is to extend the boundaries of Tintin fandom much further. There’s bound to be an overlap but I suspect there’ll be fairly distinct camps. What do you think?

R: The secret of Tintin is great storytelling, characters and illustration are timeless; they transcend any dated elements. Chang Chong-Jen said “You must marry the wind of inspiration with the bone of graphic clarity”; a metaphor perhaps only an artist like Hergé could rise to.

I think Tintin is more relevant than ever. The comic form has gained acceptance, and if teachers embrace it, Tintin could become a cornerstone for graphic literature in education. It’s not just the art but the writing is also a model of refinement. I always take a box of books when I teach a class and Tintin is always the first to be grabbed. Remedial readers especially love it and they’re mainly boys; why not give them what they love and affirm that comics are real reading.

One more for the road: your favourite Tintin image?

Mine is the full page of Tintin supporting Haddock in through the desert after the crash, Snowy leading the way . It’s the essence of the books: adventure with a heart.

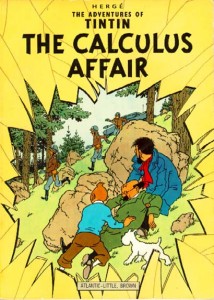

H: Perhaps I’ll pick the cover of The Calculus Affair, which works well artistically (three friends, the two most important with their heads turned from us so that they, like us, are focused on three foes, the angles of the slope and bodies, etc.) as well as depicting my favourite characters in shared danger. So much in it. Where are they? How did they get here? Why is Calculus unconscious? What does the cracked glass mean? Who are those uniformed men? And — best of all — what happens next?

H: Perhaps I’ll pick the cover of The Calculus Affair, which works well artistically (three friends, the two most important with their heads turned from us so that they, like us, are focused on three foes, the angles of the slope and bodies, etc.) as well as depicting my favourite characters in shared danger. So much in it. Where are they? How did they get here? Why is Calculus unconscious? What does the cracked glass mean? Who are those uniformed men? And — best of all — what happens next?

R: The adventure begins! Thanks for the feast, Hergé.