Archive for the ‘Book Reviews’ Category

Friday, May 22nd, 2015

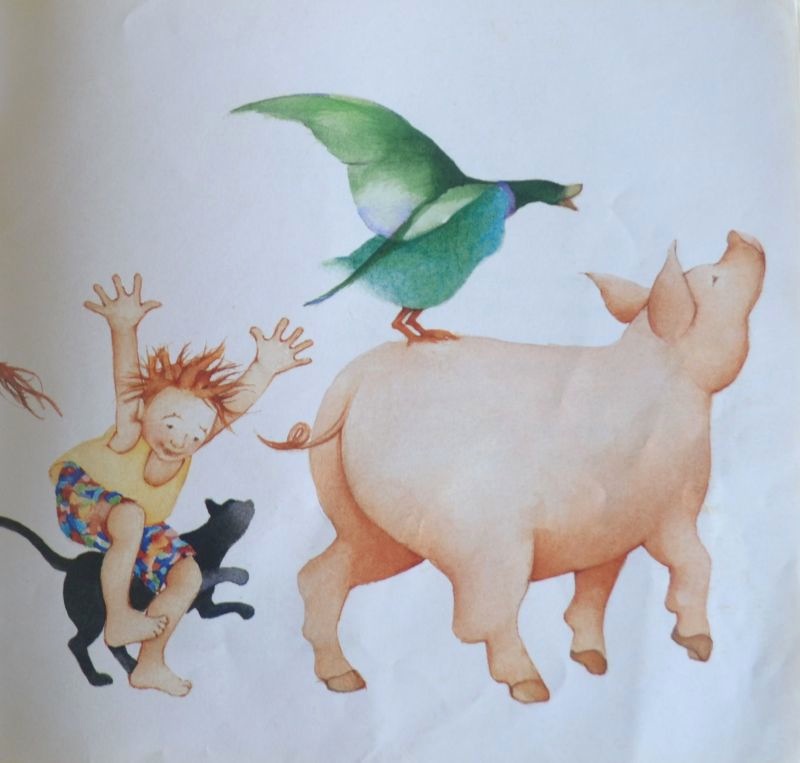

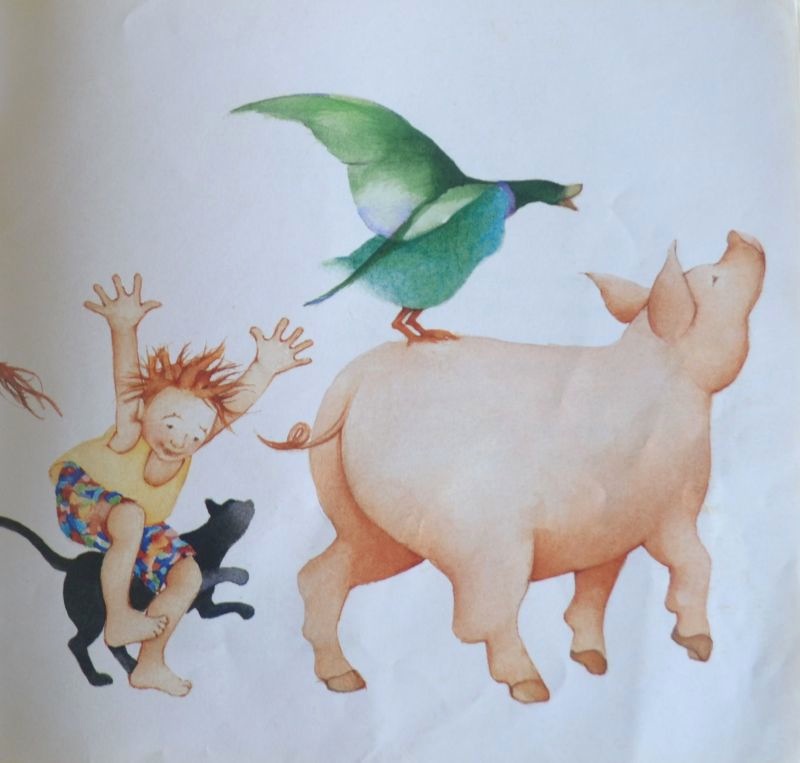

The best picture books are like a marriage: the text and illustrations support each other but have a strong life of their own. For very young children the plot should be focused and the pictures comforting. I Went Walking by Sue Williams is a perfect first book. The words are basic yet they incorporate repetition, questions, rhymes and humour. And the illustrations by Julie Vivas are sublime; leading the eye across the page in a dance of line, shape and colour. (See her gorgeous version of the Nativity too).

Max’s Bath by Barbro Lindgren is another delightful book for preschoolers. Max dumps his toys and his food in the tub and then tries to wash the dog with predictable results. Max is a classic ‘terrible two year old’ combining charm and mischief.

The picture book Seasons by French artist, Blexbolex is a unique, meditative book for young children that adults will relish for it’s design. It’s a tactile treat, printed in chunky hardback on rough paper, like old comic annuals. Each page has a single word and a subtle image to illustrate it. No garish colours here, just the quiet passing of seasons.

Tags: children's books, picture books

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Sunday, May 10th, 2015

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1940) is best loved for his exquisite fable The Little Prince, but he also wrote one of the greatest true adventures, Wind, Sand and Stars (1940), an exciting poetic, philosophical memoir. Saint-Exupéry’s flights in the 1920s and 30s took him across the Pyrenees, Andes, and the Sahara in a tiny plane that would sometimes conk-out “with a great rattle like the crash of crockery.” There are remarkable descriptions of flying among waterspouts in a typhoon and his survival after a crash in the desert (which inspired The Little Prince).

In the sky a thousand stars are magnetized, and I lie glued by the swing of the planet to the sand. A different weight brings me back to myself…Behind all seen things lies something vaster; everything is but a path, a portal or a window opening on something other than itself.

Tags: books, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews | 3 Comments »

Sunday, February 8th, 2015

One evening, a Sufi stopped by the roadside to read a book. He lit a bright lamp then walked some distance away and lit a small candle. He sat by the candle and read. People passing by asked, “Why don’t you read by the lamp?” The Sufi replied, “The bright lamp attracts all the moths. Here I can read my book in peace.” (Adapted from A Perfumed Scorpion by Idries Shah)

Blockbuster books attract many readers, but I’m attracted by books that are almost forgotten. Here are a few favourite hidden gems:

- Till We Have Faces by C. S. Lewis retells the myth of Cupid and Psyche; and which Lewis called “far and away the best of my books.”

- Catastrophe, the strange stories of Dino Buzzati – a brilliant collection of surreal stories.

- Daydreamer by Ian McEwan – imaginative stories about a boy who daydreams to cope with growing up.

- The Importance of Living, by Lin Yutang – thoughts on everything by a Chinese writer and inventor

- Drift by William Mayne – survival story about a North American Indian girl and a white boy.

Tags: books, Reading, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews | No Comments »

Sunday, February 1st, 2015

A Bee in a Cathedral by Joel Levy is a fascinating book of science analogies and astonishing numbers. Suitable for all ages, only the physics section is a bit complex. A few of my favourites factoids:

- Every day 1 million meteoroids strike the Earth

- How far to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri? Travelling in a rocket at 250,000km/h, it would take you 18,000 years

- Most of the living cells in your body are less than a month old

- About 50 million neutrinos are passing through you now

- Every molecule in a glass of water is changing partners billions of times a second.

- How hard does your heart pump blood? Empty a bathtub in 15 minutes using only a teacup —repeat this without stopping for the rest of your life

- If an atom were blown up to the size of a cathedral, the nucleus would be no larger than a bee buzzing about in the centre.

Tags: books, honey bees, reviews, science

Posted in Bees, Book Reviews, Science | No Comments »

Sunday, January 4th, 2015

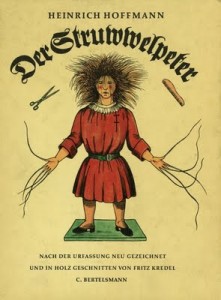

The book has long oscillated between being accepted as harmless hilarity and being condemned as excessively horrifying- Humphrey Carpenter

Struwwelpeter (Pretty Stories and Funny Pictures) by Dr Heinrich Hoffman (1845) is a classic of gleefully gruesome cautionary rhymes about naughty children. Hoffman was a psychiatrist who founded an influential Frankfurt asylum and pioneered counselling as an alternative treatment to cold baths. The characters in Struwwelpeter were inspired by his child patients – he’d tell them stories and draw pictures to calm them down. Hoffman was looking for a book for his three year old son and could only find ‘stupid collections of pictures, and moralising stories’, so he created Struwwelpeter. It was one of the first picture books designed purely to please children – before 1850 children’s books were mainly religious and moral lessons with titles such as An Exact Account of the Conversion, Holy Lives and Joyful Deaths of Several Young Children. Read more about ‘Shock-Headed’ Peter here.

The Awful Warning carried to the point where Awe topples over into helpless laughter.– Harvey Darton

Tags: children's books, picture books, reviews, struwwelpeter

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books, Humour, Reading | No Comments »

Saturday, December 6th, 2014

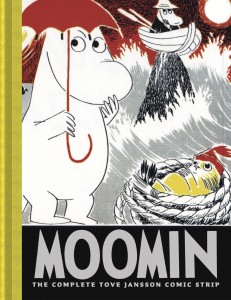

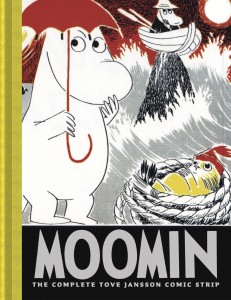

There is great exuberance in the Moomins, and a delightful battyness. – Jeanette Winterson

The Moomin comic strips by Tove Jansson (originally from the 1950s) are reprinted in five magnificent hardback volumes. The comics are a lovely balance of humour and optimistism. The free-spirited Moomins live in the moment and these comics are still relevant, commenting on consumerism, the environment and work. For example, in The Conscientious Moomins, an officer of the League of Duty admonishes Moominpappa for being a drop-out; but when Moominpappa joins the establishment, all the pleasure goes out of his life, and he returns to his old philosophy of

‘Live in peace, plant potatoes and dream!’

Tags: children's books, comics, moomins, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books, Humour, Peace | No Comments »

Sunday, November 23rd, 2014

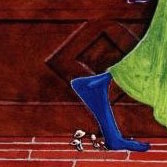

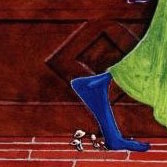

The Grey Lady and the Strawberry Snatcher is a classic picture book that almost didn’t make it. It took Molly Bang years to create and it was repeatedly rejected by publishers – they said it was ‘peculiar-looking’ and that ‘children won’t relate to an old woman as a protagonist’. The manuscript sat in a drawer for years, was re-worked and finally published to some critical reviews, writes Molly Bang: ‘The New York Times that said that the weird-looking characters and flashy colors were an indication that I was part of the drug culture and the detailed pictures told no real story but were merely an excuse to show off.’ Then it won a Caldecott award and everything changed. Why? It’s a one-of-a-kind, off-the-wall book, and very creepy! I love the tiny fungi that grow where the Strawberry Snatcher has trod.

Tags: children's books, picture books, writing

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books, Writing | No Comments »

Sunday, August 24th, 2014

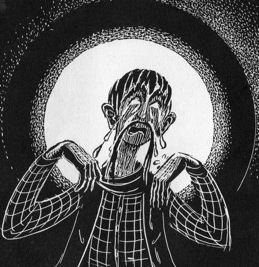

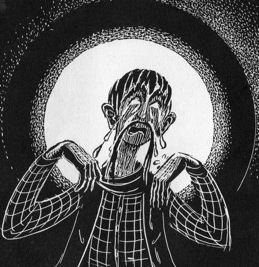

The classic picture book Calico the Wonder Horse — The Saga of Stewy Stinker by Virgina Lee Burton was published in 1941. I adored this comic-book style cowboy adventure as a child mainly because of the bad guy. Stewy Stinker is so low he steals Christmas presents from children but in the end he repents. This picture of him crying out his rottenness always made me feel sorry for him:

The word ‘Stinker’ was censored from the book in the 1940s as it was considered inappropriate for children. Burton was one of the great illustrators and the idea for Calico from seeing her sons engrossed with comic books. The wonderful design, cartoon framing and action scenes of Calico are worthy of a modern graphic comic: the flash flood and stagecoach crash are gripping highlights. But it’s that haunting image of Stewy that will stay with me.

Tags: children's books, picture books

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Sunday, July 27th, 2014

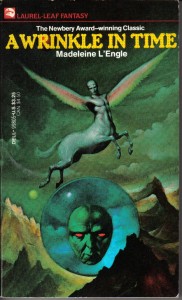

I loved science fiction when I was a young teen – especially short stories about time travel, which usually had surprise endings. In Arthur C Clarke’s All the Time in the World, a man freezes time a second before a nuclear blast; in A Sound of Thunder, by Ray Bradbury, the death of an insect changes the course of history. I still have my old copy of Bradbury’s Golden Apples of the Sun; the Corgi paperback cost me 65 cents new in 1970 (about the hourly rate for raspberry picking in my summer holidays). A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle was a novel ahead of its time in 1960 (it was rejected 26 times by publishers). Its plot combines wormholes and angels and has a classic ending: a giant disembodied alien brain is defeated by love. L’Engle liked to tackle grand themes, as she said:

You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.

Tags: children's books, Ray Bradbury, science fiction

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books, Sci-Fi | No Comments »

Saturday, May 31st, 2014

Old Tibet was once the essence of the mystical in Western eyes: with tales of mysterious Shangri-La and the yeti; the remote Himalayas; the serenity of Buddhism and its Dalai Lama. This essence has influenced many comic stories, such as wartime hero, Green Lama (1945), who got his strength by reciting a peaceful Buddhist mantra. Tintin (1958) experienced the power of Tibet when led by a vision to find a lost friend – even the Dalai Lama praised Tintin in Tibet.

Old Tibet was no paradise but, sadly, the culture is fading fast. China invaded in 1950 and destroyed 6,000 Buddhist monasteries; and in 1959 the Tibetans rose up and thousands died. There’s since been a long struggle against the occupation – some Tibetans want independence, others (like the Dalai Lama) would settle for religious freedom and some autonomy.

Tags: comics, tibet, Tintin

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Tuesday, April 22nd, 2014

‘There are moments, Jeeves, when one asks oneself, “Do trousers matter?”’

‘The mood will pass, sir.’

P.G. Wodehouse (WOOD-house) created a world without earthquakes, wars or dictators (except Roderick Spode whose ‘eye that could open an oyster at sixty paces’); where nothing mattered, except tidy trousers, and nothing broke, except engagements. He was a brilliant writer who cooked up similes like a master chef:

His legs wobbled like asparagus stalks.

She looked like a tomato struggling for self-expression.

Her face was shining like the seat of a bus-driver’s trousers.

Wodehouse published 90 books, writing until his death at 93 years. When asked about his technique he said ‘I just sit at a typewriter and curse a bit’. All his books make me happy, but my favourite is Right Ho, Jeeves, about Bertie Wooster and his valet, Jeeves, who is ‘so dashed competent in every respect’. The chapter where Gussie Fink-Nottle presents the prizes at a private school is a great example of slow-building comedy.

Wodehouse published 90 books, writing until his death at 93 years. When asked about his technique he said ‘I just sit at a typewriter and curse a bit’. All his books make me happy, but my favourite is Right Ho, Jeeves, about Bertie Wooster and his valet, Jeeves, who is ‘so dashed competent in every respect’. The chapter where Gussie Fink-Nottle presents the prizes at a private school is a great example of slow-building comedy.

The sheer joy of stories which offer a world where things come right.– Sophie Ratcliffe (Wodehouse, Letters)

Read Stephen Fry’s tribute to P.G. Wodehouse.

Tags: books, humour, reviews, writers

Posted in Book Reviews, Humour, Writing | No Comments »

Friday, March 28th, 2014

This is a wonderful collection for children aged 8-12… Museums are hives of story, both real and imagined. These 22 authors have created new stories surrounding some intriguing objects from Te Papa Museum… Raymond Huber writes one of the most memorable stories in the collection, of a unique breed of humans who mature into insects (a highly original allegory). – Sarah Forster

Tags: children's books, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Thursday, February 27th, 2014

Comics were banned in WW2 occupied France but Edmond-François Calvo secretly produced a powerful satirical comic that became a French icon after the Germans retretaed in 1944. La Bete Est Morte! is the story of the bloody European war told with Disney-style animal characters: with the French as rabbits; British bulldogs; and German wolves (Goebbels is a weasel, Himmler a skunk). La Bete Est Morte! is a forerunner of the brilliant graphic novel, Maus, with its Nazi cats and Jewish mice. Here’s an extract:

Comics were banned in WW2 occupied France but Edmond-François Calvo secretly produced a powerful satirical comic that became a French icon after the Germans retretaed in 1944. La Bete Est Morte! is the story of the bloody European war told with Disney-style animal characters: with the French as rabbits; British bulldogs; and German wolves (Goebbels is a weasel, Himmler a skunk). La Bete Est Morte! is a forerunner of the brilliant graphic novel, Maus, with its Nazi cats and Jewish mice. Here’s an extract:

My dear little children, never forget this: these Wolves who perpetrated these horrors were ordinary Wolves … They were not in the heat of battle excited by the smell of powder. They were not tormented by hunger. They did not have to defend themselves, nor to take vengeance for a victim of their own. They had simply received the order to kill.

Tags: books, children's books, comics

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Monday, February 10th, 2014

Alice Walker’s picture book Why War Is Never a Good Idea begins with the bright, comforting colours of a book for young children, but as War devastates the land the images become grim. It’s a scary message and parents will have to judge if it suits their children. The illustrations by Stefano Vitale are evocative and Walker’s words are true:

Though War is old

It has not become wise.

Though War has a mind of its own

War never knows who it is going to hit.

Walker comments: ‘War attacks not just people, “the other,” or “enemy,” it attacks Life itself … It doesn’t matter what the politics are, because though politics might divide us, the air and the water do not … Our only hope of maintaining a livable planet lies in teaching our children to honor nonviolence, especially when it comes to caring for Nature, which keeps us going with such grace and faithfulness.’

Tags: children's books, non-violence, Peace

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books, Peace | No Comments »

Tuesday, January 14th, 2014

You must marry the wind of inspiration with the bone of graphic clarity.– Chang Chong-Jen.

The Adventures of Herge is a must for Tintin geeks although it’s not for children. It’s a Hergé (George Remi) biography done in the ‘clear line’ style of a Tintin comic book. Hergé fell in love with drawing in 1914 when his mother gave him some pencils to ‘calm him down’. The book is a fascinating insight into the influences on Hergé and the political and emotional difficulties he faced, especially during wartime working under the Nazis. Most moving of all is the story of his friendship with Chang Chong-Jen (which inspired Tintin in Tibet). Chang helped him refine his beliefs and drawing style. Before reading this book it might help to know a bit about Hergé, or to read the appendix first.

The Adventures of Herge is a must for Tintin geeks although it’s not for children. It’s a Hergé (George Remi) biography done in the ‘clear line’ style of a Tintin comic book. Hergé fell in love with drawing in 1914 when his mother gave him some pencils to ‘calm him down’. The book is a fascinating insight into the influences on Hergé and the political and emotional difficulties he faced, especially during wartime working under the Nazis. Most moving of all is the story of his friendship with Chang Chong-Jen (which inspired Tintin in Tibet). Chang helped him refine his beliefs and drawing style. Before reading this book it might help to know a bit about Hergé, or to read the appendix first.

Tags: comics, writers

Posted in Book Reviews | No Comments »

Monday, December 23rd, 2013

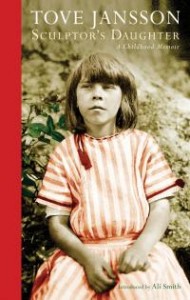

A book whose small, huge work is the healing of the divisions between the child state and the adult state; of a child-sized truth about how things connect. – Ali Smith

The Christmas present I couldn’t resist opening early: Sculptor’s Daughter by Tove Jansson is a beautifully written childhood memoir that reads more like short stories. Jansson was the creator of the charming Moomin books had a Moomin-like family: affectionate, creative, and liberal. Her parents were well known Finnish artists: her father a sculptor, her mother an illustrator. She spent much of her childhood on the Pellinki islands in the Gulf of Finland. This new edition of the 1968 book is an exquisite little hardback.

The Christmas present I couldn’t resist opening early: Sculptor’s Daughter by Tove Jansson is a beautifully written childhood memoir that reads more like short stories. Jansson was the creator of the charming Moomin books had a Moomin-like family: affectionate, creative, and liberal. Her parents were well known Finnish artists: her father a sculptor, her mother an illustrator. She spent much of her childhood on the Pellinki islands in the Gulf of Finland. This new edition of the 1968 book is an exquisite little hardback.

Tags: books, moomins, reviews, writers

Posted in Book Reviews | No Comments »

Monday, November 18th, 2013

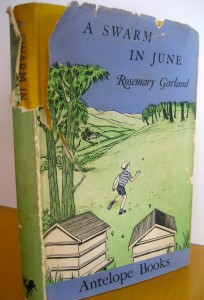

Children’s fiction about honey bees is rare and this gem from 1957 is hard to find. A Swarm in June by Rosemary Garland is a charming junior novel that beautifully combines bee lore with childhood wonder. Seven year old Jonathan finds a wild swarm in June (‘worth a silver spoon’) but a visiting cousin is scared of bees. It takes an attack by a stoat to unite the cousins in the end. It’s an innocent tale and the bee wisdom is timeless: beating a gong to attract a swarm; tracking bees with thistledown; and ‘telling the bees’ about important events in our lives. Best of all is the way the boy is so comfortable around the bees.

Tags: children's books, honey bees, reviews

Posted in Bees, Book Reviews, Children's Books | 1 Comment »

Thursday, October 17th, 2013

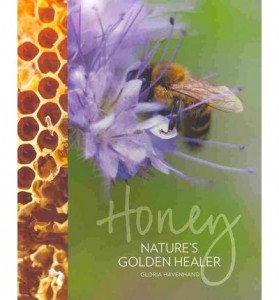

Honey, Nature’s Golden Healer by Gloria Havenhand is a superb book that deftly balances bee science, beekeeping expertise, folklore and health tips. Honey is more than just another spread for your toast:

‘Most people know very little about honey and its healing powers… Research has shown honey deserves to move into the serious league for healing.’

I thought I knew every fascinating fact about honey but I found many new insights here:

- Beeswax is made by bees only 10 to 18 days old who consume about 10 kg of honey to make 1 kg of wax.

- A little honey before bedtime fuels the brain overnight because the live stores the sugar (fructose).

- Raw honey is best to eat. Most supermarket honey is treated which removes vitamins, anti-bacterials and pollen nutrients.

- Always scrape out the honey jar – that last 1/10 of teaspoon represents the honey collected by one bee in her entire lifetime.

Tags: books, honey bees, reviews

Posted in Bees, Book Reviews | No Comments »

Sunday, August 11th, 2013

There’s a real tenderness and occasional profundity stitched into them. – Helen Brown (Telegraph)

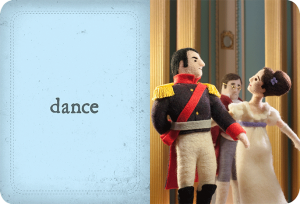

It shouldn’t work but it does. Classic novels including War and Peace, Pride and Prejudice and Oliver Twist as board books for babies. Each book is cleverly condensed into twelve words suitable for very young children. The secret is in the charming photographs which tell the story with hand-made felt dolls posed in famous scenes from the novels (not the gruesome bits). The books are simple, funny and will appeal to adults as much as children. The series is Cozy Classics.

Picture 1: Elizabeth Bennett gets muddy on the way to Netherfield.

Picture 1: Elizabeth Bennett gets muddy on the way to Netherfield.

Picture 2: Andrei and Natasha dance; Pierre is jealous.

Tags: books, children's books, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Thursday, August 1st, 2013

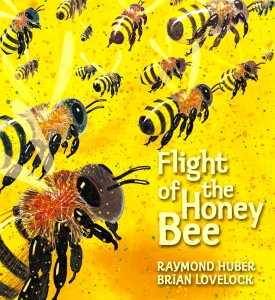

This handsome, respectful volume deserves a place on the shelf … it succeeds in accurately dramatizing honeybee behavior. – Kirkus Reviews

Flight of the Honey Bee review by artist, Claire Beynon:

“Given the state of our environment, the sooner we introduce our children to bees – to their intelligence, their intricate behaviour and increasing vulnerability – the better. Flight of the Honey Bee is the perfect book to do this, combining as it does Raymond Huber’s careful language and well-researched text with Brian Lovelock’s meticulously observed paintings. Cleverly formatted, fiction and non-fiction – story and fact – are woven together as two discreet yet interconnected strands: young readers can choose their flight path.

Exquisite to look at and a pleasure to explore.

Scout the bee – named after the feisty protagonist in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird – and her tightly-knit community of hardworking bees demonstrate these small creatures’ importance in the pollinaton of plants and the well-being of our planet. Flight of the Honey Bee is about bee behavior but it will also teach children about subtler things; wonder, beauty, the value of group functioning and collaborative effort, reproduction, risk, courage, the joys of flight – those rhythms and principles essential for any thriving community. The hum of the parts.

Scout the bee – named after the feisty protagonist in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird – and her tightly-knit community of hardworking bees demonstrate these small creatures’ importance in the pollinaton of plants and the well-being of our planet. Flight of the Honey Bee is about bee behavior but it will also teach children about subtler things; wonder, beauty, the value of group functioning and collaborative effort, reproduction, risk, courage, the joys of flight – those rhythms and principles essential for any thriving community. The hum of the parts.

This book has all the essentials of a satisfying story: it asks questions and it informs. It invites observation and participation. There’s drama. Suspense. Conflict. Danger. Hope. And a happy ending. At the close of her adventure, Scout is a wily-er bee than she was when she set out from her hive on her first nectar-seeking adventure. As all characters must, she grows through her experiences. We come to care about her and her safe passage home.

Visually, Flight of the Honey Bee is exquisite to look at and a pleasure to explore – each double page spread is as stunning as the one preceding it. It will be immediately appealing to young readers. I was struck by how beautifully integrated the text and images are; they belong together like honey and honeycomb. The language is tender and witty (the line about ‘sun-powder’ is a wonderful change from ‘gun-powder’); and the paintings – a combination of watercolour, acrylic ink and coloured pencils – are spectacular; compositionally bold, delicate, exuberant and information-rich. Looking at them through my adult eyes, I can’t help thinking about fractals, the mathematics inherent in nature, the ever-present background dialogue between shape and sound, pattern and colour. Children will pore over them. And they will love Scout for her feisty resourcefulness.

More Flight of the Honey Bee reviews.

Tags: children's books, picture books, reviews

Posted in Bees, Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Wednesday, May 15th, 2013

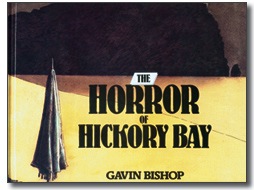

Here are three of my favourite New Zealand picture books that give children a manageable dose of horror. Gavin Bishop’s Horror of Hickory Bay has grown on me over the years. The story of a bland family on a Canterbury beach and an amorphous beast seemed a bit coarse to me 25 years ago, but now I love the earthy monster (which has a new force in quakey times). Diane Hebley said it best:

I find this book fascinating for its masterly use of colour and design, its grim humour, its coherence of idea, text and image, and for its acceptance of the dreamworld reality.

The Were-Nana by Melinda Szymanik is a creepy delight about a visiting relative who might just be a monster. The suspense is nicely built up and the double surprise ending (true to horror traditions) is brilliant. Odd cover choice but fine shadowy illustrations by Sarah Nelisiwe Anderson.

Te Kapo the Taniwha by Queen Rikihana-Hyland is out of print but was always popular in class. It’s the story of a half-man, half-monster who was given the job of shaping the South Island. Zac Waipara’s pictures are stunning as usual.

Tags: children's books, picture books, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Saturday, May 4th, 2013

Three neglected science fiction books by New Zealand writers:

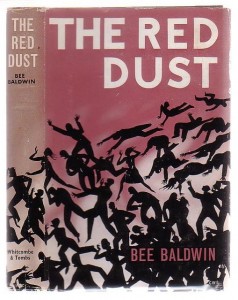

The Red Dust by Bee Baldwin (1965) is one of the first NZ post-apocalyptic novels. A deadly red dust released by Antarctic drilling wipes out much of the world. A group of immunes must survive roaming gangs and a mastermind who wants to rule New Zealand. It’s a chilling, well-structured story, with great use of NZ settings (this adult novel was inexplicably in my primary school library where I read it at age 10 and understood about 10%).

The Unquiet by Carolyn McCurdie is a strikingly original intermediate novel and a suspenseful read. It has an apocalyptic opening when the planet Pluto and parts of the Earth’s surface vanish. A small town girl has a gift for sensing unrest in the fabric of the universe and becomes the focus in a battle as the novel turns into a fantasy.

Where All Things End by David Hill describes a spectacular journey into a Black Hole. A mission to study the hole goes wrong and the crew race towards the Singularity- a point where all things become no-things. A ripping yarn underpinned by a convincing depiction of space travel and universal theories.

Tags: books, reviews, science fiction

Posted in Book Reviews, Sci-Fi | No Comments »

Friday, January 11th, 2013

At last! The original Moomin book has been released in an elegant hardcover English edition for the first time. Moomins and the Great Flood (1945) is a junior novel that reveals the Moomin’s origins. Moominmamma and her son leave the world of humans (where they lived behind stoves) and become refugees, seeking their lost beloved, Moominpappa, who has been swept away by a flood. We meet the characters who will populate the later novels: Sniff, the Hemulen, the Antlion and the surreal Hattifatteners, who “did not care about anything except travelling from one strange place to another.” This poignant story was Jansson’s response to the Second World War that had interrupted her painting career. The book has her beautiful atmospheric watercolours.

At last! The original Moomin book has been released in an elegant hardcover English edition for the first time. Moomins and the Great Flood (1945) is a junior novel that reveals the Moomin’s origins. Moominmamma and her son leave the world of humans (where they lived behind stoves) and become refugees, seeking their lost beloved, Moominpappa, who has been swept away by a flood. We meet the characters who will populate the later novels: Sniff, the Hemulen, the Antlion and the surreal Hattifatteners, who “did not care about anything except travelling from one strange place to another.” This poignant story was Jansson’s response to the Second World War that had interrupted her painting career. The book has her beautiful atmospheric watercolours.

Reading this book in the light of the suffering of the Finnish people in 1939 as they were caught up in the turmoil of their Winter War casts a different glow over what is essentially a classic adventure story.– Esther Freud

Tags: children's books, moomins, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews, Children's Books | No Comments »

Sunday, January 6th, 2013

Why Does The World Exist? by Jim Holt is a fascinating book that asks the question, ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’ Holt looks at all sides of the question, interviewing scientists, philosophers, atheists and believers (Richard Swinburne, John Irving, Roger Penrose, Adolf Grunbaum…). There are three types of theorist:

The “optimists” hold that there has to be a reason for the world’s existence and that we may well discover it. The “pessimists” believe that there might be a reason for the world’s existence but that we’ll never know for sure… Finally, the “rejectionists” persist in believing that there can’t be a reason for the world’s existence, and hence that the very question is meaningless.

Leibniz’s Principle of Sufficient Reason says that ‘For every thing there must be a reason for that thing’s existence‘, which is the basis of our scientific worldview. Holt does a good job of summarizing some knotty philosophy, physics and maths (understanding it is another matter!). Although he offers no firm answers, the book left me feeling “optimistic”; and it’s oddly comforting that after picking the brains of the world’s greatest thinkers, Holt concludes,

No one can confidently claim intellectual superiority in the face of the mystery of existence.

Photo: Solar eruption, Dec 31, 2012 – courtesy of NASA Images

Tags: books, connections, reviews, science, Universe

Posted in Book Reviews, Science, Universe | No Comments »

Monday, December 17th, 2012

The Science Delusion by rebel scientist Rupert Sheldrake challenges the current scientific dogma that life is mechanical and purposeless. His chapters ask: “Are the laws of nature fixed? Is nature purposeless? Are minds confined to brains?” The title is a bit misleading but perhaps it’s a dig at Richard Dawkins (of ‘God Delusion’ fame), who describes living things as ‘machines’. The US edition title is Science Set Free, and it’s Sheldrake’s aim to break free from rigid materialistic science. Anyone who has ever had a pet, kept bees or grown a tree, knows that plants and animals are living organisms with a sense of purpose, not just an assembly of chemicals:

The Science Delusion by rebel scientist Rupert Sheldrake challenges the current scientific dogma that life is mechanical and purposeless. His chapters ask: “Are the laws of nature fixed? Is nature purposeless? Are minds confined to brains?” The title is a bit misleading but perhaps it’s a dig at Richard Dawkins (of ‘God Delusion’ fame), who describes living things as ‘machines’. The US edition title is Science Set Free, and it’s Sheldrake’s aim to break free from rigid materialistic science. Anyone who has ever had a pet, kept bees or grown a tree, knows that plants and animals are living organisms with a sense of purpose, not just an assembly of chemicals:

All living organisms show goal-directed behaviour. Developing plants and animals are attracted towards developmental ends…Even the most ardent defenders of the mechanistic theory smuggle purposive organising principles into living organisms in the form of selfish genes and genetic programs.– Rupert Sheldrake

Even the smallest entities seem to have a form of consciousness. He describes remarkable single-celled swamp creatures, called Stentor (photo), which have a memory despite having no nerve endings (synapses). Sheldrake writes most lucidly about science and philosophy, and he’s not afraid to theorise about fringe science events (which he explains with his rather cryptic theory of ‘morphic fields’). Read a review.

swamp creatures, called Stentor (photo), which have a memory despite having no nerve endings (synapses). Sheldrake writes most lucidly about science and philosophy, and he’s not afraid to theorise about fringe science events (which he explains with his rather cryptic theory of ‘morphic fields’). Read a review.

Tags: consciousness, reviews, science

Posted in Book Reviews, Science | 2 Comments »

Thursday, December 13th, 2012

This is not the end of the book is a fascinating conversation between two great bibliophiles, the author Umberto Eco and film-maker, Jean-Claude Carriere. They discuss the history of the physical book and our digital future. It’s a rambling, wide-ranging conversation (as the best are) and the enthusiasm of these book lovers swept me along. And there’s an especially fine chapter on book censorship.

This is not the end of the book is a fascinating conversation between two great bibliophiles, the author Umberto Eco and film-maker, Jean-Claude Carriere. They discuss the history of the physical book and our digital future. It’s a rambling, wide-ranging conversation (as the best are) and the enthusiasm of these book lovers swept me along. And there’s an especially fine chapter on book censorship.

The Internet has returned us to the alphabet … From now on, everyone has to read… Alterations to the book-as-object have modified neither its function nor its grammar for more than 500 years. The book is like the spoon, scissors, the hammer, the wheel. Once invented, it cannot be improved.’ – Umberto Eco

Tags: books, Reading, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews, Reading | No Comments »

Saturday, August 18th, 2012

It is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition. And, it lies between the pit of man’s fears and the summit of his knowledge. – Rod Serling (The Twilight Zone)

Catastrophe, the strange stories of Dino Buzzati (1949) is a brilliant collection of surreal stories. Each deals with a  disaster and many have an allegorical mood. People are trapped on a train rushing towards an unknown cataclysm; a reporter searches for a elusive landslide; a rich family refuses to believe there’s a flood outside their house.

disaster and many have an allegorical mood. People are trapped on a train rushing towards an unknown cataclysm; a reporter searches for a elusive landslide; a rich family refuses to believe there’s a flood outside their house.

Buzzati wrote Catastrophe after WW2 and it reflects the fears of the time. My favourite is a kind of parable about dictatorship in which a bat-like creature terrorizes a household. A more satirical story has an epidemic of ‘state influenza’ which attacks only those opposed to the government. The scariest tale is about a hospital with seven floors that lead a patient either upwards or downwards, towards life or death.

These bizarre, suspenseful stories reminded me of the best of The Twilight Zone which also walked the fine line between real and imaginary (eg. the episode Nick of Time) .

Fantasy should be as close as possible to journalism.– Dino Buzzati

Tags: books, reviews, twilight zone

Posted in Book Reviews | No Comments »

Tuesday, July 3rd, 2012

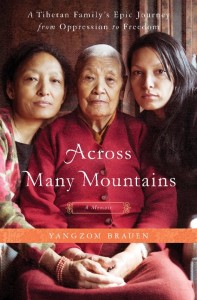

Book review: Across Many Mountains by Yangzom Brauen is the remarkable true story of three generations of women from one Tibetan family, who encompass cultural extremes from old Buddhist Tibet to Hollywood glitz. The first part of the book is a gripping account of an escape, via the Himalayas, from the brutal Chinese invasion of 1950 ( which fulfilled a 1,200 year old Buddhist prophecy: ‘The Tibetan people will be scattered like ants across the face of the earth‘.) Part two is fascinating because of the culture clash when the Tibetans experience Western ‘civilisation’. When the family finally return to Tibet in the 1980s they find ‘a country that has been robbed of its soul’. The Chinese have suppressed the language and culture (and still do). But the book is even-handed and also has a warts-and-all picture of Old Tibet where Buddhism was influenced by folk religion. The 90 year old grandmother-nun, Kunsang, is the heart of this inspiring book.

Book review: Across Many Mountains by Yangzom Brauen is the remarkable true story of three generations of women from one Tibetan family, who encompass cultural extremes from old Buddhist Tibet to Hollywood glitz. The first part of the book is a gripping account of an escape, via the Himalayas, from the brutal Chinese invasion of 1950 ( which fulfilled a 1,200 year old Buddhist prophecy: ‘The Tibetan people will be scattered like ants across the face of the earth‘.) Part two is fascinating because of the culture clash when the Tibetans experience Western ‘civilisation’. When the family finally return to Tibet in the 1980s they find ‘a country that has been robbed of its soul’. The Chinese have suppressed the language and culture (and still do). But the book is even-handed and also has a warts-and-all picture of Old Tibet where Buddhism was influenced by folk religion. The 90 year old grandmother-nun, Kunsang, is the heart of this inspiring book.

Book group discussion notes.

Recent news about Tibet

Tags: books, political change, reviews

Posted in Book Reviews | No Comments »

Tuesday, February 28th, 2012

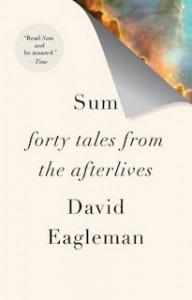

Sum, Forty Tales from the Afterlives, by David Eagleman, is a hugely entertaining, often thought-provoking book. Each very short story describes a quirky version of life after death. There is an afterlife populated only by people you remember; one where you are split into different ages; another where God is a married couple. Listen to Stephen Fry reading one about a highly ordered afterlife. The stories are not so much about theology or God (although He, She, and They do appear as somewhat fallible characters) as about treasuring the life we have now – plus a bit of humour and sci-fi just for fun. Here’s a video interview with Eagleman (a neuroscientist) who describes himself as a ‘Possibilian’– one who explores new ideas. (More novels about the afterlife).

Sum, Forty Tales from the Afterlives, by David Eagleman, is a hugely entertaining, often thought-provoking book. Each very short story describes a quirky version of life after death. There is an afterlife populated only by people you remember; one where you are split into different ages; another where God is a married couple. Listen to Stephen Fry reading one about a highly ordered afterlife. The stories are not so much about theology or God (although He, She, and They do appear as somewhat fallible characters) as about treasuring the life we have now – plus a bit of humour and sci-fi just for fun. Here’s a video interview with Eagleman (a neuroscientist) who describes himself as a ‘Possibilian’– one who explores new ideas. (More novels about the afterlife).

Tags: books, science fiction, Universe

Posted in Book Reviews, Sci-Fi, Universe | No Comments »

Saturday, February 18th, 2012

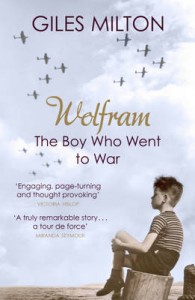

I’ve read many books about Hitler’s Germany but none as remarkable as Wolfram, The Boy Who Went To War, by Giles Milton (Hodder, 2011). It overturns clichés about the War and helps answer the old question ‘Why didn’t more Germans resist Hitler?’

I’ve read many books about Hitler’s Germany but none as remarkable as Wolfram, The Boy Who Went To War, by Giles Milton (Hodder, 2011). It overturns clichés about the War and helps answer the old question ‘Why didn’t more Germans resist Hitler?’

Wolfram was the child of freethinking, artistic parents who resisted by not joining the Nazi Party and refusing to display a swastika flag – their Gestapo file described them as ‘dangerous eccentics’. Wolfram was 9 years old when Hitler came to power in 1933 and spent his childhood trying to avoid the Hitler Youth so he could draw and sculpt. Through his peace-loving family we see how the Nazis tightened their grip through brutality, laws, and a system of local informants.

One can’t help ask, ‘Would I have had the courage to resist?’ Wolfram was conscripted and became part of the War nightmare in Russia and Normandy. The story of his survival is completely gripping. (Note: not a children’s book, but would interest teens.) Wolfram is still alive and you can see his stunning paintings here.

This is a study in enforced conformity as Milton shows how the Nazis became increasingly intrusive in the lives of ordinary Germans Guardian review

Tags: books, Peace, war

Posted in Book Reviews, Peace | No Comments »

At last! The original Moomin book has been released in an elegant hardcover English edition for the first time. Moomins and the Great Flood (1945) is a junior novel that reveals the Moomin’s origins. Moominmamma and her son leave the world of humans (where they lived behind stoves) and become refugees, seeking their lost beloved, Moominpappa, who has been swept away by a flood. We meet the characters who will populate the later novels: Sniff, the Hemulen, the Antlion and the surreal Hattifatteners, who “did not care about anything except travelling from one strange place to another.” This poignant story was Jansson’s response to the Second World War that had interrupted her painting career. The book has her beautiful atmospheric watercolours.

At last! The original Moomin book has been released in an elegant hardcover English edition for the first time. Moomins and the Great Flood (1945) is a junior novel that reveals the Moomin’s origins. Moominmamma and her son leave the world of humans (where they lived behind stoves) and become refugees, seeking their lost beloved, Moominpappa, who has been swept away by a flood. We meet the characters who will populate the later novels: Sniff, the Hemulen, the Antlion and the surreal Hattifatteners, who “did not care about anything except travelling from one strange place to another.” This poignant story was Jansson’s response to the Second World War that had interrupted her painting career. The book has her beautiful atmospheric watercolours.